HSC Candidatures - A Worrying Trend

Are HSC students choosing easier options rather than those that are best for their futures?

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”

Mark Twain, and probably someone else before him.

I want to write about some worrying (to me) trends in student candidature numbers in the HSC. But it’s important to note that numbers are very difficult to ascribe meaning to. I think there’s enough here to make some general conclusions, but I may well be wrong. This is complex and there is no data to point to a single most likely causation. I’d be surprised if there is a single cause for what I want to show. Why things look like they do is complex and complicated. Why things are changing is equally so.

Senior students in the NSW HSC are changing their study patterns. This isn’t new. There will always be ebbs and flows in the interests and priorities of populations. But the direction being taken right now is not one I’m comfortable with by any means.

There are lots of charts to see here, relating to a heap of subjects. They’re pretty much all the same, just relating to different subjects. I guess just look at what you’re interested in.

Changing Cohorts

Let’s start with a high level summary, albeit a little simplistic, to set the tone.

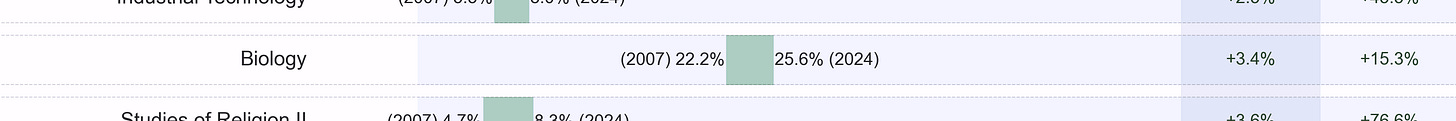

This chart shows the change in numbers of students stdying some courses in the NSW HSC. These are the subjects I’d propose have experienced the most significant changes in candidature relevant to their populations in 2007 and 2024. In order to show on this chart, a subject has to have had 500 or more students in either 2007 or 2024 and it has to have had a greater than 0.5% variation in enrolments compared to the population from 2007 to 2024.

So in English Advanced, in 2007 the candidature was made up of 43.7% of all HSC students. In 2024, 34.7% of all HSC students participated in English Advanced. The difference between those two numbers is 9%. The proportional difference is the difference of the percentage of the 2007 proportion as a percentage of the 2024 proportion. I've included that because moderate changes in small cohorts may be, as proportions of the population, more significant than larger differences in larger cohorts.

IDT exam has seen a -2.6% change in candidature compared to the NSW populations at the time, but has seen a -83.9% change in candidature according to its own populations as proportions of the NSW populations.

The proportional difference column on the right is the one to pay the most attention to.

Population

Defining a population is surprisingly difficult. For these charts, I’ve used the UAC Scaling Report numbers that include every student who completed at least one ATAR contributing subject in that year. As such, students who complete no ATAR eligible subjects are excluded and students who accelerate in such subjects will count for more than one year.

2007 NSW HSC population: 65,005

2024 NSW HSC population: 74,291

The 2024 population was unusually large.

English

The biggest red bar here is English Advanced. Here’s what it looks like in a bit more detail.

Although the candidature in 2024 wasn’t the smallest in absolute terms, relative to the population it was. In 2007, 43.2% of NSW HSC students studied English Advanced. In the 2024 HSC, that number is 34.2%.

In 2007, about 90.9% of students studied English Standard and Advanced. Although 2 unit English is compulsory, it’s never 100% of the cohort studying it because of accelerants (I’ve never seen an student accelerating in English), schools running a compressed HSC curriculum and other oddities and anomalies.

In 2024, that has dropped to about 78.6% of HSC students studying Advanced or Standard.

Here’s what English Standard candidature looks like from 2007 to now.

Changes in cohort sizes in both Standard and Advanced are difficult to ascribe meaning to. There’s a definite, steady decline in cohort sizes in Advanced, but it is slow. In 2019 English Studies was introduced with an optional exam to allow it to count to a student’s ATAR. This sits below English Standard, so it shouldn’t have affected the Advanced cohort. In 2024, at the count of students in courses in September, there were 10,069 students enrolled in English Studies. According to UAC, 1,491 of those students sat the exam. That 1,491 students represents about 2% of all NSW students.

Here are the English Studies Exam cohorts since 2019.

There’s lots to see here, in 2 unit English. There’s a new course to count to students’ ATARs, there’s the same new course pulling thousands of students out of the ATAR pool, there’s drops in enrolments in both Standard and Advanced.

But the drop in Advanced students can’t be ignored. The drop in English Advanced is a drop of 9% of the entire HSC population, but it’s 20% of English Advanced students. From 2007 to now, there are, proportionately, only 80% as many students in English Advanced as there have been in the past. That is far, far too many for me to be comfortable with. Fewer students are taking on the more difficult 2 unit English course than ever before.

English Extension is showing similar trends. Here’s English Extension 1.

Just over six thousand students completed English Extension 1 in 2007. This has dropped to just below four thousand. That’s a significant drop by any account. But when the population is taken into account, that’s a 46.3% drop in the proportion of English Extension 1 students (see the chart right at the top).

English Extension 2 is similar.

Fewer students in English are choosing to study the harder thing.

English Extension is about to undergo big changes. Teachers begged NESA not to do what they are going to do. NESA acknowledges stakeholder feedback was negative. They’re going to go ahead and do it anyway.

Looking for reasons why this is happening is important. There have been quite a lot of observations made about this and I’m sure they’re valid. People are reading less across all ages. Course content is no longer relatable or relevant. There’s too much time in class on screens. There’s not enough time in school on computers.

But, as I want to show, this isn’t an English problem. It’s a school problem.

What I want to hold on to from this is that the biggest decline we’ve seen across English enrolments is in the most difficult subjects on offer.

Mathematics

Maths is not immune from all of this either, but Maths is a beast of its own.

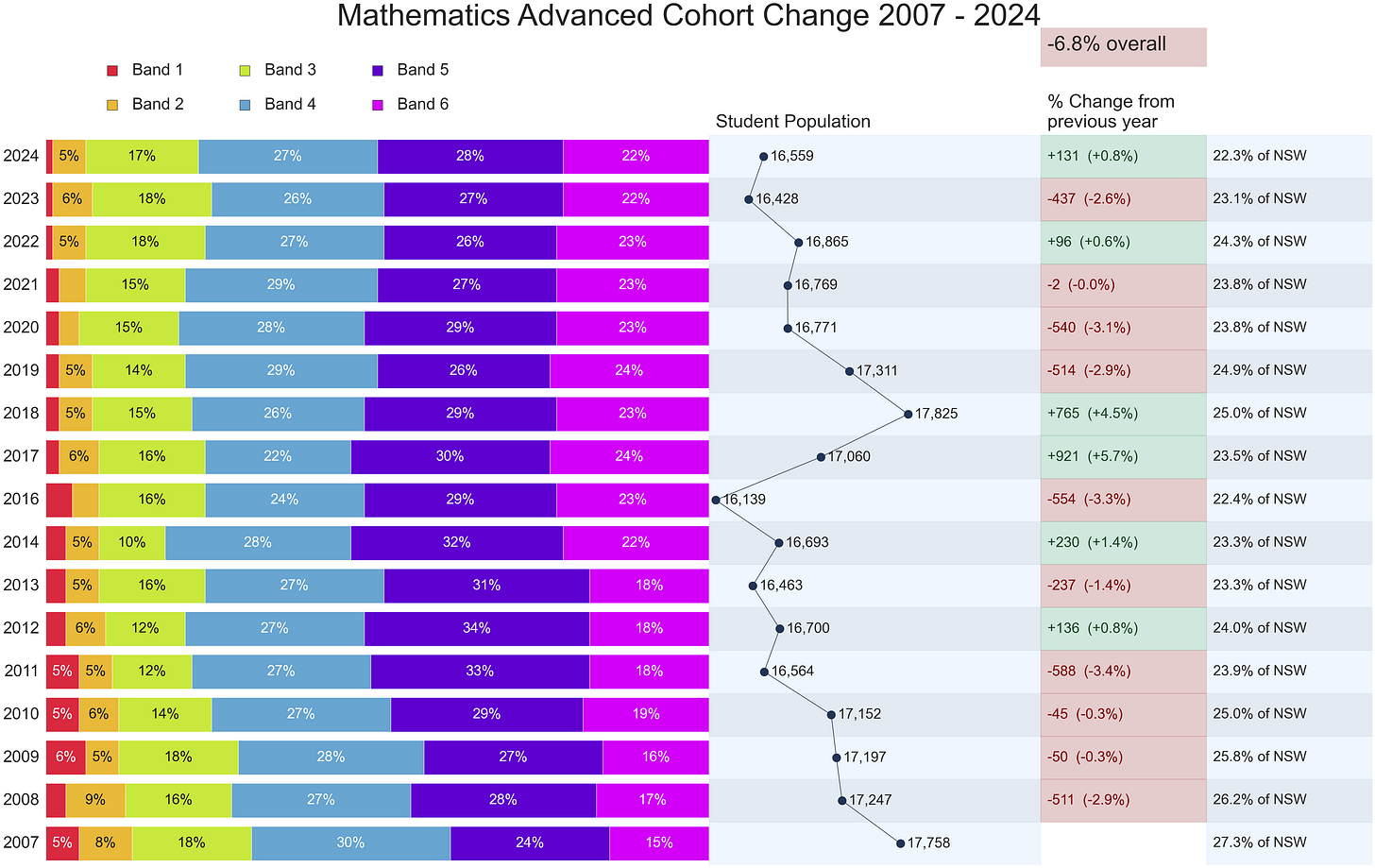

Here’s Maths Advanced in that summary chart right at the top of this post.

The proportional drop in Maths Advanced candidature is 18.3%, not dissimilar to English Advanced.

From 2007 to now, Maths Advanced has lost 1,000 students a year in real terms and 18% of its proportional population.

The following chart labels the past as maths Standard 2, but if you know the past, you know that pre-2019 was slightly different.

The numbers here don’t explain the drop in Maths Advanced. I think there are a few reasons for this, but one of them is Maths Standard 1.

I don’t need to go through it all again, it’s not dissimilar to English, but there is an added option of dropping Maths altogether.

In both English and Maths, we’re not just seeing students dropping out of the hardest courses, what I think we’re seeing is students choosing not to take the path that’s difficult for them. For a growing number of students for whom Maths Standard 2 is a real challenge, there’s now an option of Studies and it’s being taken up more readily than it has been in the past.

Maths Extension 1 is, I think, an important subject in the HSC to take a good look at each year. It’s which has, against all odds, maintained its high academic status and strikes fear into the hearts of students. Extension 2 doubly so.

Maths Extension 1 is seeing smaller changes in its population than English Extension 1, but according to the chart right at the top, from 2007 to 2024 has seen a 10.5% drop in proportional candidature.

That’s a big drop. It’s a big drop in a subject that is very resilient. Mthematics Extension 1 is fueled by high achieving public, Catholic and independent schools. Of course it’s offered almost everywhere, but the esteem in which Mathematics is held in the parental culture of high achieving schools far exceeds that of English. The money spent on tutoring students for Maths vs English must be many multiples. But even with that, Maths Extension 1 candidature is shrinking.

I don’t know how reasonable it is, but I see Maths Extension 1 as a litmus test and the results are concerning.

Maths Extension 2 has also seen proportional decline, although it is less than Extension 1. This is at least a good thing, I think, although its direction is still concerning.

English and Maths

What I’m seeing here in English and Maths concerns me greatly. Fewer students are taking the courses that are harder for them.

That, in and of itself, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I don’t want students who aren’t well equipped for English Advanced to be in English Advanced. Similarly, a student who’s not ready to start learning calculus should not be in Mathematics Advanced. It’s not that learning calculus is particularly difficult. It’s that you need to be at a certain point of readiness to be likely to succeed. For most students who aren’t ready for Maths Advanced, it’s not that they’re incapable. It’s that they’re not ready yet. I assume the same is true of English Advanced. Although I know it’s more complex than just that.

What I am putting forward here, though, is that an increasing proportion of students are studying what is perceived to be the easier option when, for some at least, and I would propose an increasing proportion, they are capable of struggling through the more challenging or rigorous course.

When you take the easier option you don’t grow as fast or as far.

Science

Science is seeing change in candidatures along the lines of English and Maths, but with some differences.

Chemistry is the 2 unit subject in the HSC with the best reputation for scaling. There are an awful lot of students wh obelieve that choosing Chemistry will result in their marks being ‘scaled up’. They’re wrong, there’s no such thing as scaling up. But the reputation persists, regardless.

Despite this, Chemistry’s candidature is in decline.

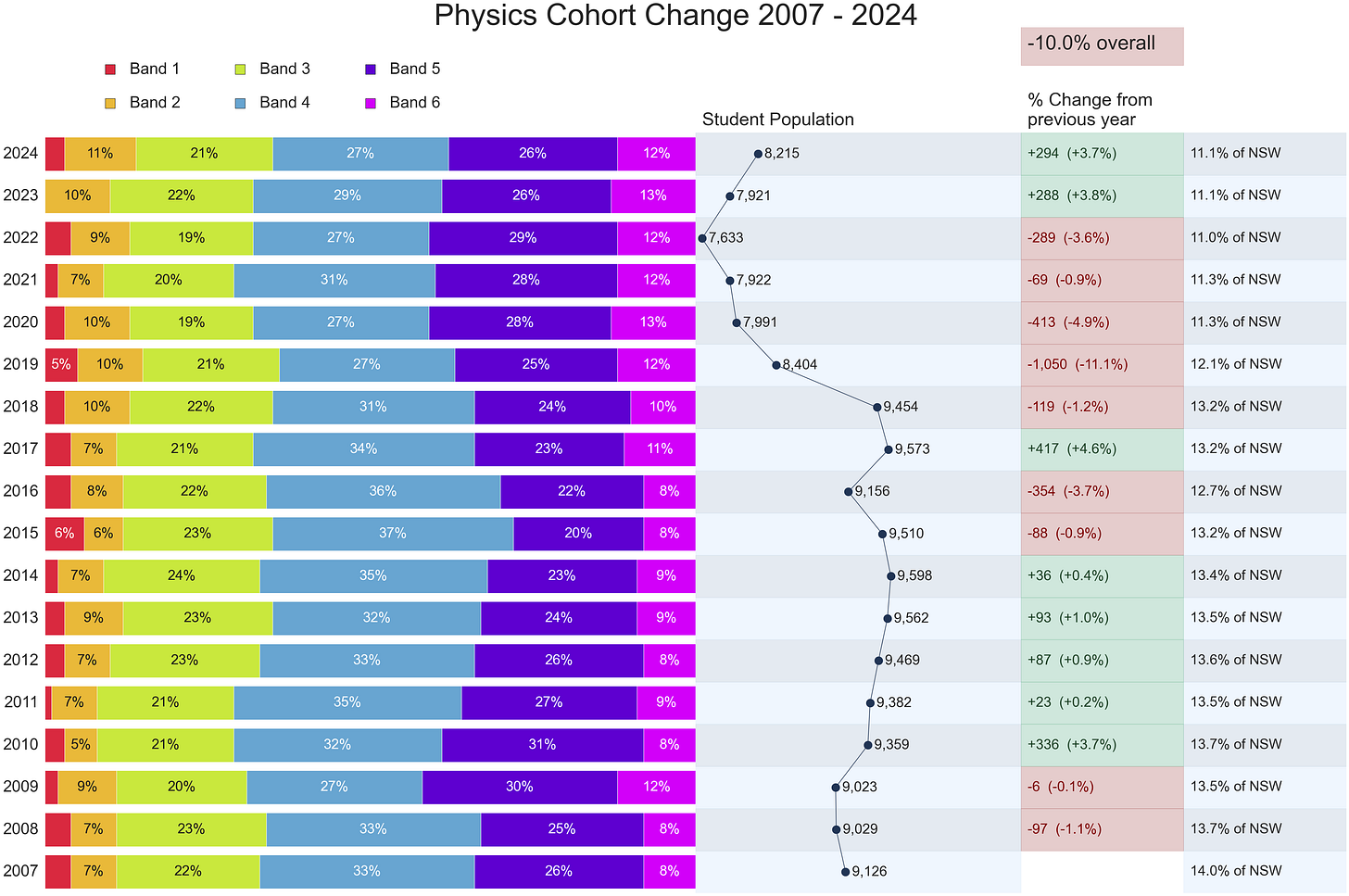

Physics and Chemistry, both, are seeing significant proportional declines in candidature.

Science teachers have, for quite some time now, been pointing out the obvious truth that Band 6 acheivement in their subjects is being set at a threshold that’s really high.

When you look at the most difficult Band 6 thresholds to cross, according to scaling, you see that the most difficult 2 unit Band 6 scores to achieve are Chemistry, Physics, Latin Continuers and Biology. Then it’s 2 unit English.

For Science to have three of the four most difficult Band 6 thresholds is not insignificant. Then EES is 10th. In a world that’s Band 6 obsessed (NESA and the SMH conspire together for this abomination to persist), this is a big deal for Science.

Biology and EES, though, do not have the changing trends in enrolments that Chemistry and Physics have.

In 2024, Biology did have a change in cohort and was overtaken by Business Studies as the most studied non Maths or English course. But over time, the change in population is positive with a 15.3% proportional increase from 2007 to 2024.

I want to be careful what I communicate here. Biology is not an easier science. But at school, it’s perceived as such compared to Physics and Chemistry. In the last few years its growth has stagnated, still. I suspect we’re seeing the beginning of a decline in it’s candidature.

EES has, like Biology, seen an increase in candidature, both in real and proportional terms, especially in the last six years.

An 84% proportional increase in candidature for EES is nothing to scoff at. It’s a subject on the rise.

Investigating Science is still fairly new.

Starting with Maths Standard 1 and English Studies, as well as Science Extension, it’s still finding its feet, I think.Candidatures are increasing nd changing. I think it needs more time to know what it is to students across the state.

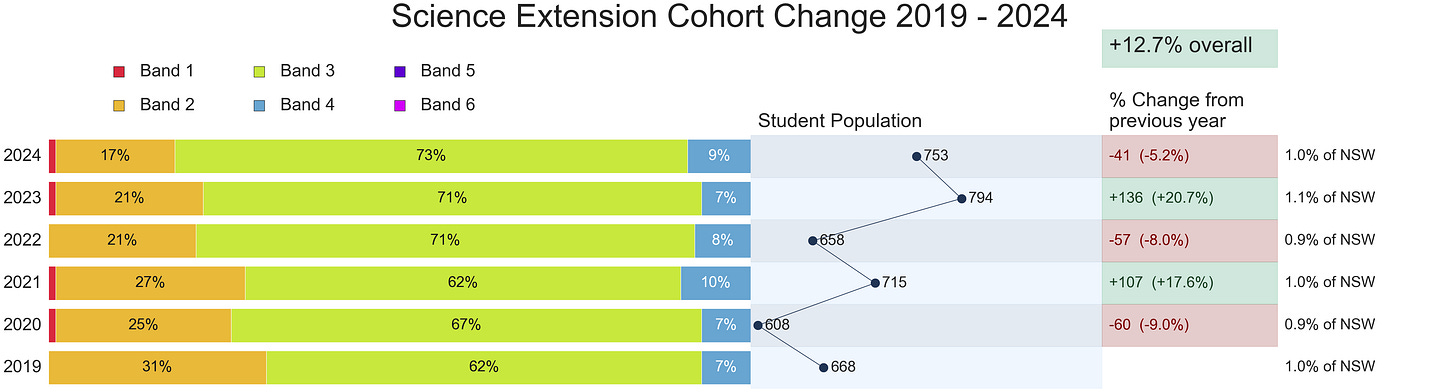

I think similarly about Science Extension.

E4 acheivement in Science Extension is really low compared to every other extension subject. This is a problem that NESA would do well to rectify. But I can’t see them doing that.

I think it’s clear. Students are walking away from Chemistry and Physics. I don’t like it one bit.

HSIE

Overall, HSIE subjects have remained relatively consistent. There are some notable exceptions, though.

Ancient History has seen a significant decrease in candidature with a proportional decrease of about 40% of students from 2007 to 2024.

2024 did see a significant increase in candidature from 2023, though. I hope that’s a sign of things to come. Recent government obsession with turning university into job training, along with the success of the constant repetition of the term ‘STEM’, has hurt humanities subjects by making them unreasonably expensive to study after school. Hopefully this will change in the future.

Modern History, in comparison, has not experienced such a decline.

History Extension is also down, with a 27.3% proportional decrease in candidature.

Business Studies is on the up.

In 2024, over a quarter of all NSW HSC students were studying Business Studies.

Proportionally, the change isn’t meteroric. But when you’re at the top, what more looks like slows down.

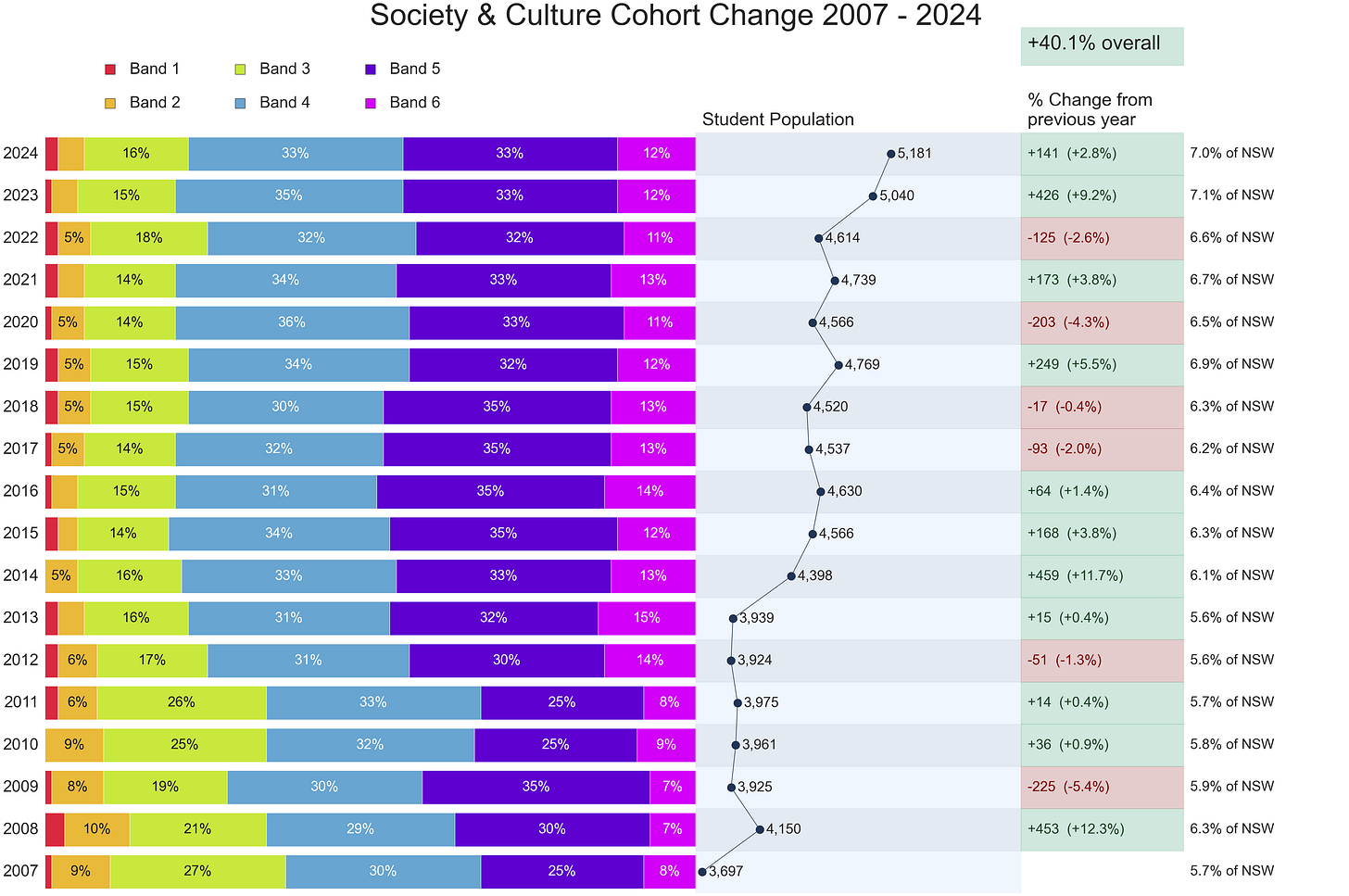

Society and Culture candidature is increasing, with a 22.8% proportional increase in candidature.

Geography is down. I find Geography candidature perplexing. It’s heavily influenced, I think, by Stage 5 timetabling, but in ways that History is not. Maybe I just find Geography perplexing, I’m not sure.

Economics is a subject that matters to this conversation, I think.

Candidature in recent years has been rising, but overall the change from 2007 to 2024 has been negative, with a proportional drop of 13.8%.

PDHPE & CAFS

Both PDHPE and CAFS are the larger subjects with the most consistent growth, outpacing the growth of all HSC students.

So What?

I’m not saying that subjects that are growing are subjects that shouldn’t. I’m pleased for a rise in candidature in CAFS. It’s a good subject that speaks to lots of aspects of life that other subjects don’t.

But I am concerned about the trend of decreasing candidatures in more challenging subjects.

Doing hard things matters. As someone much wiser than me expressed it the other day, I want students to squeeze as much as they can from their education. I don’t think you’re doing that if you’re ready to deal with the next hard thing, but you choose the easier road instead.

It’s not that you need to do every hard thing. It’s not that every student should be in the most difficult courses. It’s not that if you don’t learn calculas, you’ll have some kind of academic deficit for the rest of your life.

But at the same time, what comes after school is difficult. Success in the world is difficult. Especially if the odds are stacked against you. Taking on hard things in school is good practice. It makes you smarter and it makes you more ready.

If you work hard in Maths Advanced and are able to experience some measure of success, I think you’re likely to come out a better mathematician than if you’d worked hard in Maths Standard 2. Maybe I’m wrong, but obviously I don’ think so right at the moment.

Disrespected and Undervalued

Schools and teachers have become punching bags for politicians, the media and the public in general. Education and school are no longer synonymous and, increasingly, school is something seen as what you need to get through before you can get to what you want to do.

This is a disastrous state of affairs. The more loud and influential adults disrespect and undermine schooling, the more students hear it and take it to heart.

But it’s more than just that. There’s been a push to devalue ambition in education. Why learn more than you need? Why memorise what you can look up? Why work today at the cost of enjoyment? You can succeed in the future despite a lack of effort today. Behind these questions and ideas are insidious lies. But the people spouting them over and over don’t realise that.

Universities Run by Shitbags

Our universities value money over anything else. They are desperate and have demonstrated they are perfectly willing to repeatedly enter young, impressionable people into significant bad debts the universities are the beneficiaries of. In NSW, The University of Sydney was the last holdout for prerequisites. In the name of competing for enrolments, they’ve abandoned them. NSW universities are in a race to the bottom. This isn’t a reflection on lectureres, researchers and other teaching staff. It’s administrators and bean counters whose values are at odds with what education is and should be about. Our federal government has, and continues to fail to hold them to account. In fact, they guarantee the loans against students’ futures. It’s no wonder that we have former federal members of parliament taking on lucrative roles as vice chancellors of our universities. I guess there are perks to not stirring the pot too much in your political career.

The current state of affairs with early entry devalues ambitious study patterns by students in their senior years of school. Studying harder subjects doesn’t feel like looking after your future when the institutions you want to attend tell you you’re in no matter what marks you get and no matter what you’ve studied.

Do What’s Good For You, Not What You Want

I don’t want students in Year 10 to be the sole determiners of the next two years of their schooling. They’re hearing from social media, from friends, from family, from an awful lot of people, that school is fine, I guess, but it doesn’t really matter. They’re battered with examples of people who’ve succeeded in life despite their lack of achievement in school. They’ve heard that NAPLAN doesn’t matter, the HSC doesn’t matter, their ATAR doesn’t matter.

Why on earth would we then expect them to turn around and make positive decisions to serve their futures well.

Schooling isn’t about having the most fun today. It’s about creating the brightest future for tomorrow. Bright futures are carved out by hard work and determination.

Ambition Matters

This is complicated. Everything is complicated. I do understand that. But I don’t care.

Education is an ambitious endeavour. I believe that education is transformative. It’s the best leveler of future opportunities. But student participation is necessary. Teaching is only a part of the equation and does not ensure learning happens. Learning is an activity of learners themselves and they need to be ambitious as well.

I think that we’re experiencing an opting out of schooling. What I’ve presented here is just one aspect of the evidence for that viewpoint, but I think a lot of educators feel it as well.

This is bad for all our futures. We need ambition back in education. We need students to believe that their education matters. Not to try to sell them something, but because it does.

Universities, the government, the media and others need to pull their heads in and stop telling children that schooling doesn’t matter. It does. If any people working in schools are undermining students’ learning by giving the impression that what happens in school doesn’t matter, that needs to stop. It does.

Students need to be encouraged to be ambitious learners. They also need great teaching so that ambition isn’t in vain.

We’re on a trajectory that won’t serve us well. It can change, though.

There are few messages that could be more important than this one — thanks Graham.

Perhaps I was unusual, even for my time, but my attitude was that for many of the subjects I studied at school (and university),even if out of necessity rather than desire, it was likely the last opportunity I would have to do so (at least in a supportive environment), so I was going to squeeze the most I could out of the opportunity.

Despite the negativism fuelled by current political and social outlooks, particularly among our young people, we need to rekindle love of learning and an appetite for knowledge.

Re; "the and probably someone else before him", I always understood "lies, damn …" was due to Benjamin Disraeli.